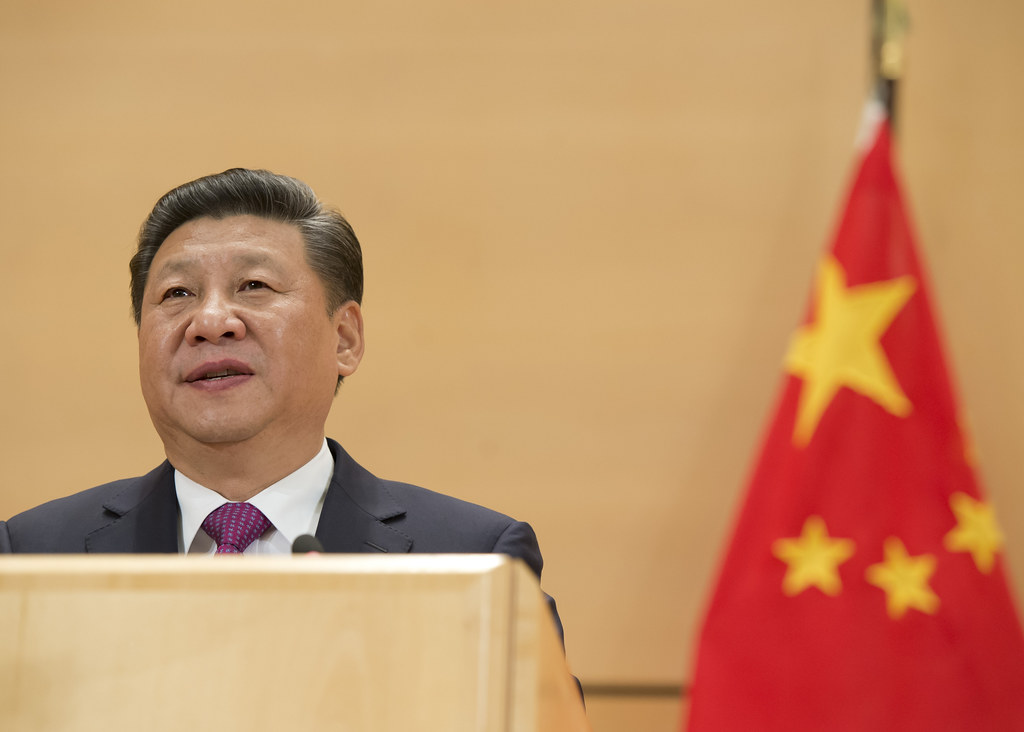

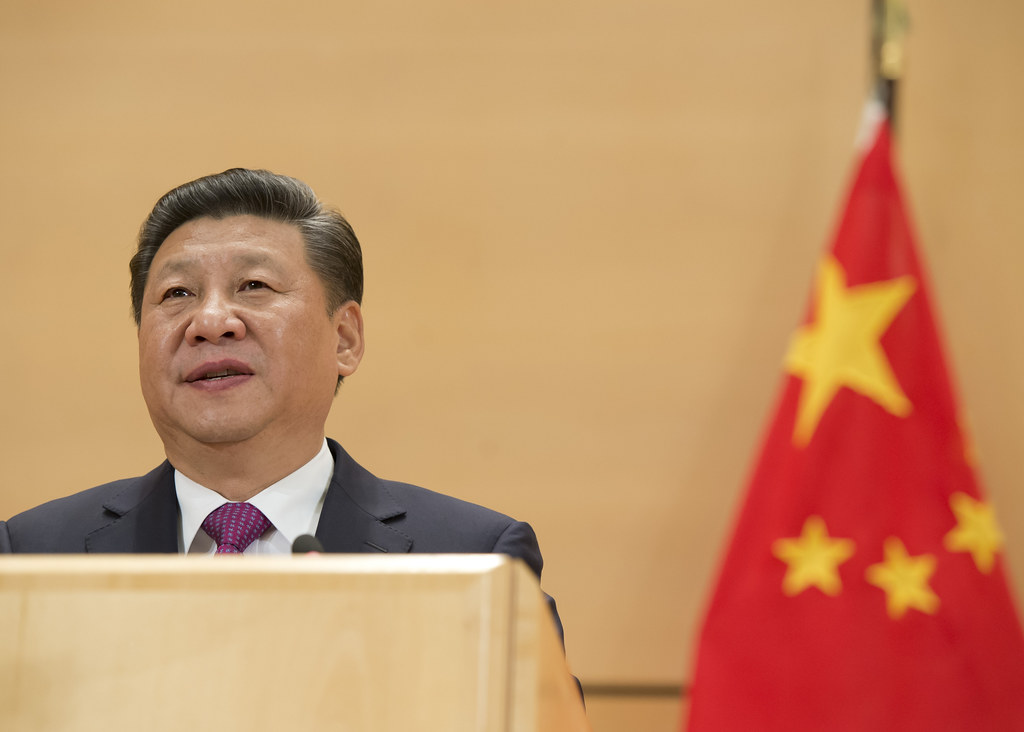

During Xi Jinping's visit to France, ECPM spoke with Marie Holzman, a sinologist specializing in contemporary China and President of the Solidarité Chine association, to review the state of the death penalty in the country. Today, while 46 charges are punishable by death, the Middle Kingdom continues to shroud the data regarding its application in mystery. Where do we stand today?

In China, central power is omnipresent, exerting tight control over all aspects of the country’s political, social, and economic life. Under Xi Jinping’s leadership, centralization has intensified, creating an atmosphere of repression where individuals’ fundamental rights are regularly violated.

China continues to heavily rely on the death penalty, with the highest number of convictions and executions in the world. Despite numerous calls from the international community to ensure respect for human rights, the Chinese government has often chosen to ignore or inadequately respond to these recommendations issued by other UN member countries.

Despite NGO calls for transparency, Chinese authorities do not disclose any data, making any estimation of executions difficult. In France, during diplomatic meetings, human rights defenders are consulted beforehand, but no concrete follow-up of the discussions held behind closed doors is provided to them. In China, data concerning the few cases of death penalty that are publicized are carefully controlled by the state and used to manipulate public opinion by instilling fear and claiming to deliver justice to crime victims. This opacity shrouds real practices and raises fears about the respect for human rights and the conditions under which the death penalty is applied.

In addition to the so-called “immediate execution” death penalty, China, since the beginning of its authoritarian regime, is the only country to practice the death penalty with reprieve, a measure that adds a unique dimension to its judicial system. Death row prisoners generally have two years to show repentance, which could potentially lead to their death sentence being commuted to life imprisonment.

In 2019, while traveling to China with his wife for their honeymoon, Australian journalist Yang Heng Jun was arrested upon arrival and then sentenced to death with a reprieve in February 2024. Accused of collusion with foreign forces, he now faces life imprisonment if his sentence is commuted.

This culture of repression now extends to Hong Kong, where the new Basic Law strengthens Beijing’s control over the city. Under the pretext of national security, authorities can now prosecute individuals abroad, thus threatening the Hong Kong diaspora and human rights activists who have fled the oppressive Chinese regime. This expansion of Chinese nuisance power beyond its borders raises concerns about the protection of fundamental rights, even outside Chinese territory.

Thus, China continues to face major challenges in terms of human rights, with an opaque death penalty enforcement policy and surveillance practices that extend internationally. In this climate of repression, the fight for the abolition of the death penalty seems more difficult than ever, leaving little hope for abolitionist activists. Executions are estimated to be in the thousands per year, a figure that could be well below reality in the country.