In some ways, a commercial real estate construction project is just like any other project. There is a start date, several interim milestones, and an end date when the property is complete and a certificate of occupancy has been issued. However, a commercial real estate construction loan is not like other loans. It is distinguished by the fact that the loan balance starts at $0 and rises over time as funds are distributed, according to a predefined “draw schedule.”

The construction draw schedule determines how and when construction loan funds are distributed. However, in order to fully understand the construction draw schedule, it is first necessary to understand several concepts related to construction lending.

First, a construction loan is not fully advanced at the time of closing. This provides the lender with some oversight of the construction process and also minimizes the amount of interest expense paid by the borrower. Instead, the lender will advance a certain amount of money to pre-fund an “interest reserve” account, and funds from that account will be used to make the loan’s monthly interest payments until construction is complete. The amount of money deposited in the interest reserve account is based on a calculation made by the lender that considers the loan amount, interest rate, and the estimated length of construction.

Second, the lender doesn’t just give money to the borrower without any sort of accountability. Instead, the borrower is required to provide a budget, sometimes called a sources and uses statement, and the lender uses it as a way to track how much money has been advanced from each line item in the budget. The borrower cannot exceed the amount budgeted for each line item, otherwise they may need to request a “change order” to move money from one line item to another.

Finally, funds are not advanced whenever the borrower asks. Instead, funds are advanced based on predetermined milestones and according to the “Draw Schedule.” In some loans, the draw schedule is fairly straightforward. For example, there could be 5 draws where each one is meant to complete 20% of the project. Or, in larger deals, the draw schedule could be more complicated with dozens or more draws that are pegged to customized milestones. In either case, the specifics will be outlined in the loan agreement.

Regardless of the specific structure of the Draw Schedule, the intent is the same. It is designed to give the lender some level of control over how and when funds are distributed. In addition, it gives the lender a chance to verify what work has actually been completed before sending money out the door. To verify completed work, the lender will hire a third-party inspector to visually inspect construction progress. The inspector will then confirm that the borrower in fact spent the funds on what they said they did. Then, construction loan funds will be disbursed.

To illustrate how a draw schedule works, assume that a borrower has been approved for a $1MM construction loan and, as part of their loan agreement, they have agreed to a 5 draw schedule where each draw is advanced when the project has reached a multiple of 20% completion. So, the draws will be distributed when the project is 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% complete.

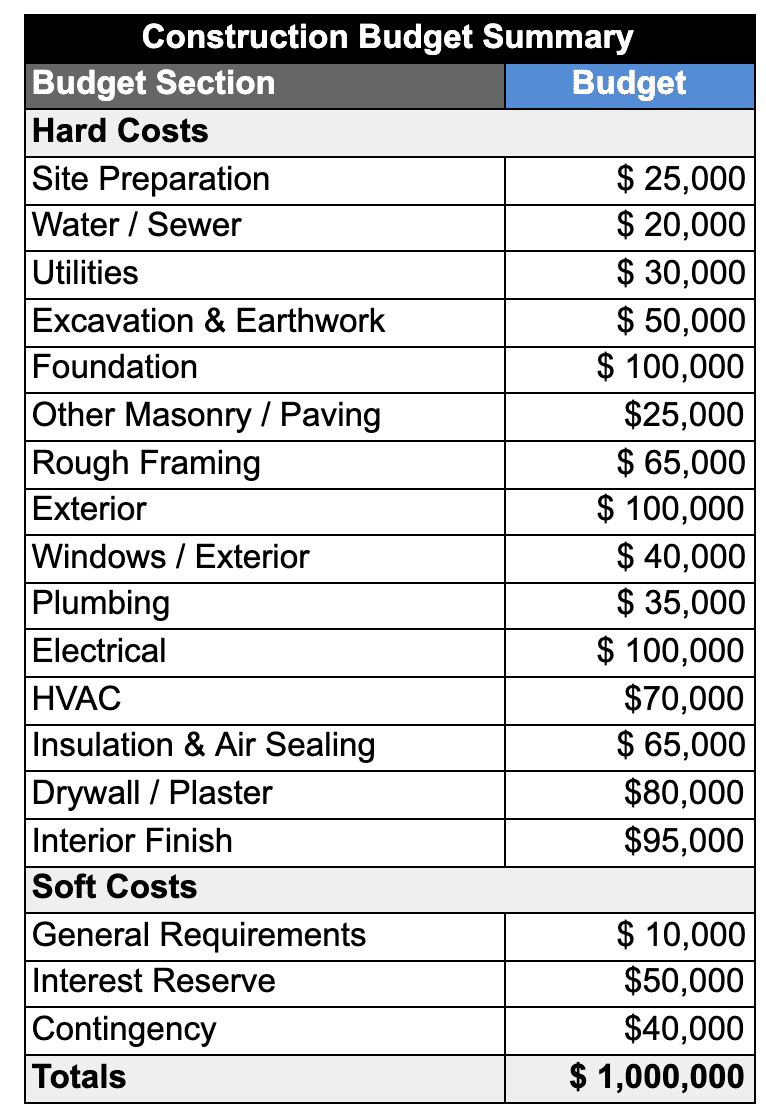

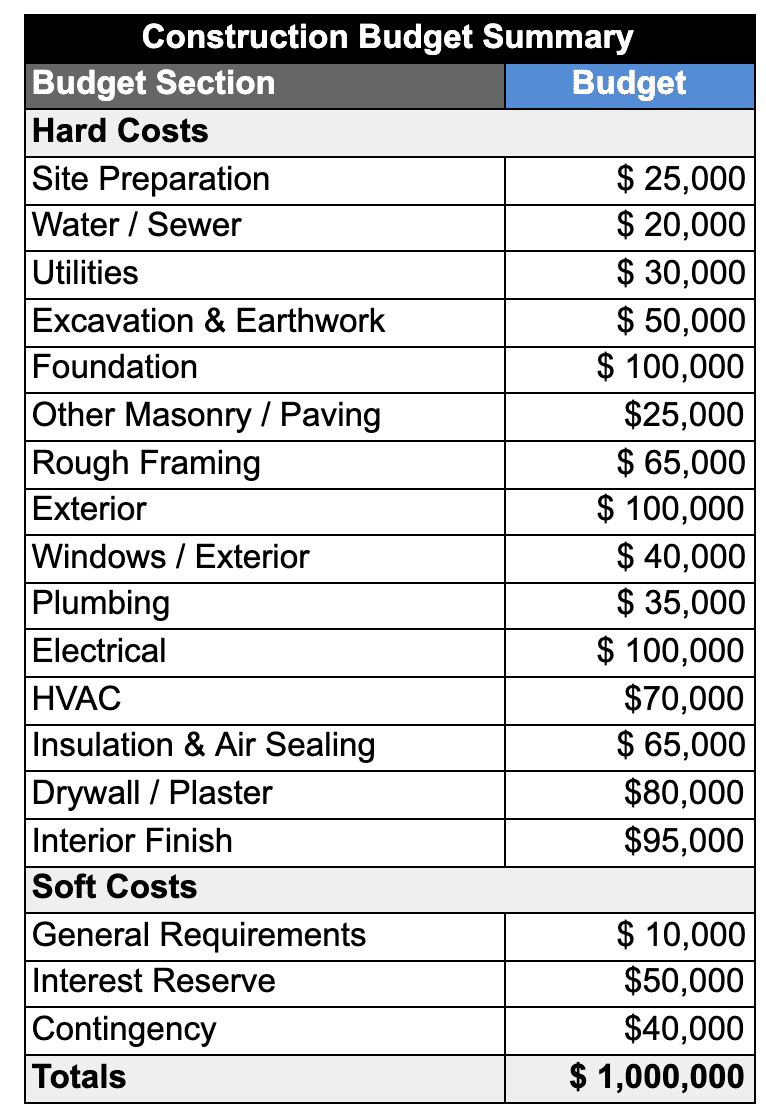

At loan closing, the borrower submits the following budget to the lender:

The lender will use this budget to set up “limits” for each one of the line items in their computer systems. So, when the builder needs funding to complete the next portion of their project, here is what happens.

First, the builder will submit a draw request to the lender. Usually, this request is submitted on an American Institute of Architects (AIA) Application and Certificate for Payment form, which is a standardized document used by many lenders and borrowers. Along with the request, they will provide some supplemental detail about which line items the money should be pulled from.

Next, the lender will hire an inspector to go to the construction site and review progress on the project. While the inspector will be looking at many details, their primary job is to confirm that the project is as far along as the borrower says it is. For example, if the borrower says they are 20% complete, the inspector will review what has been done and confirm or deny that this is the case. The inspector’s role is critical because the lender relies on their opinion and uses it as the basis for deciding whether or not to approve the draw request.

When the inspection has been completed, a report is submitted to the lender and reviewed by someone in the construction loan administration department. If approved, the draw request is processed, and funds are deducted from each line item and released to the borrower. The budget is updated in the computer systems to reflect the remaining balances on each line item. Start to finish, this process can take 2-10 days so it is always important for borrowers to consider when they need to pay their vendors and submit their draw requests ahead of the time they actually need them.

One thing that is almost always certain in a construction project is that it doesn’t go according to plan. There are almost always delays, caused by things like regulatory approvals, availability of materials, or weather conditions. For example, a sudden snow storm could shut down the job site for a day while clogging the roads and highways needed to deliver lumber or drywall to the site. As such, a 1 day weather event could lead to several days of lost time on the job site. These types of delays are important for two reasons. First, the builder likely has investors or customers who are waiting for the space to be completed and delays could upset them or lead to disruptions in their business.

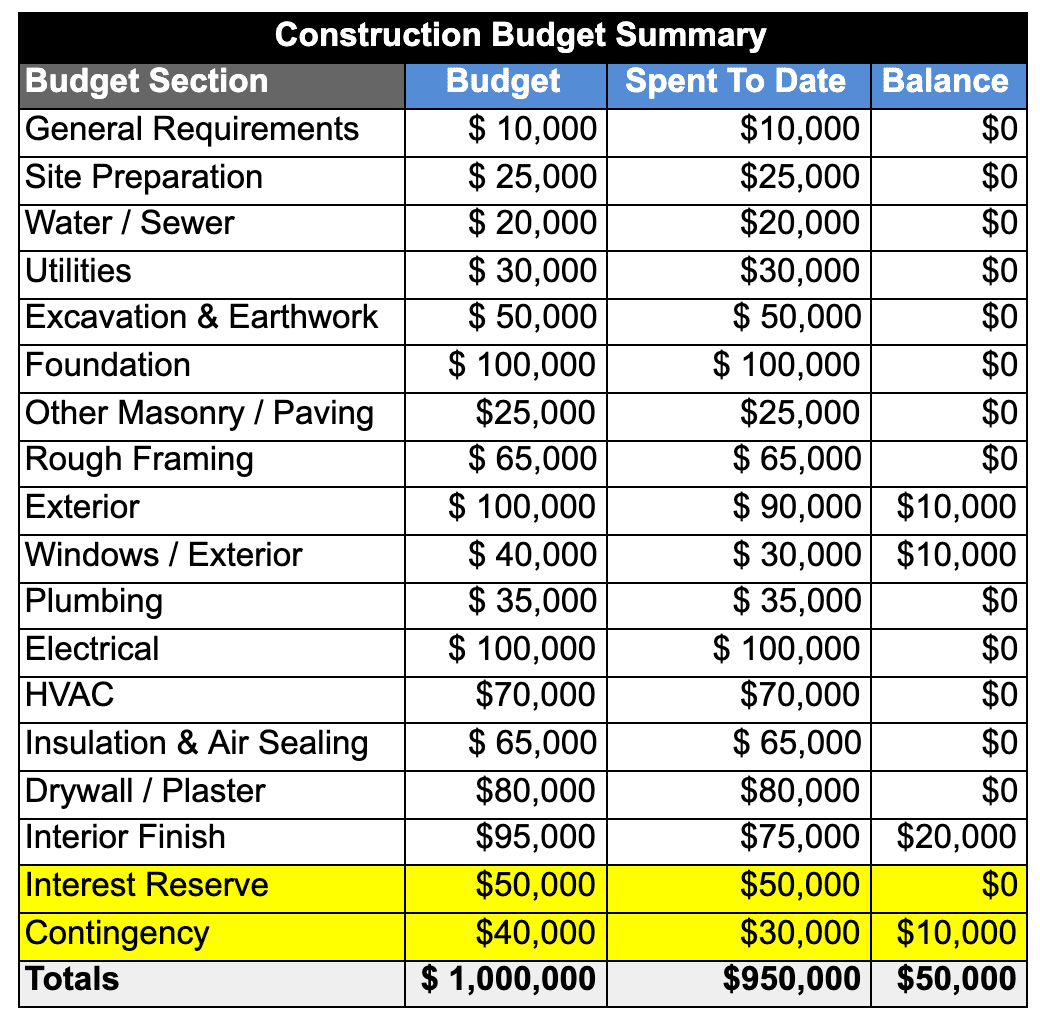

Second, and more importantly, a loan’s interest reserve calculation is predicated upon an estimate of how long it will take to complete the project. Every day the project is delayed increases the chance the interest reserve will run out before the project is completed. When this happens, the builder is faced with two options. The first is that they have to make interest payments out of their own pocket, which is never the preferred option. Or, they could ask the lender to reallocate funds from one budget line item to another, if there is availability. In some lending circles, this is referred to as a budget “change request.” For example, assume that a project is nearly complete and the allocations for several line items, including interest, have been exhausted. But, the builder needs additional funds to finish construction. The budget could look something like this:

Now, assume that the borrower is required to make a payment in order to get their final draw, but there is no money left in the interest reserve account. However, there is $10,000 remaining in the “Contingency” line item. In such a case, the borrower can make a “change request” to ask the lender to move the $10,000 from the Contingency line to the Interest Reserve line in order to make the required loan payment. Once this is done, they will be able to access the remaining funds to complete the project.

Most loan agreements state that budget line item changes will be made at the bank’s discretion, so they could deny the change request. But this usually isn’t in the bank’s best interest. The primary source of repayment for most construction loans is another permanent loan that will repay the construction loan balance. Of course, the borrower cannot obtain a permanent loan unless the project is complete. For this reason, the lender has a vested interest in seeing the project completed and is therefore unlikely to deny a change request.

A construction loan is not the same as a “regular” commercial real estate loan in two ways.

First, the loan balance is not distributed at closing, it is advanced over a series of “draws” that cause the loan’s balance to grow over time. The draws are made according to a “construction draw schedule” which is defined in the loan agreement, and specific amounts are recorded against a predetermined construction budget.

Second, interest for the loan is pre-funded based on a calculation that takes into account the anticipated length of the project, the loan limit, and the interest rate. Any delays in the project put the timeline at risk and increase the odds that the interest reserve account will run out before the project is completed. If it does run out, the borrower must make a change request to reallocate funds from one budget line item to another. Although these changes are typically made at the lender’s discretion, the lender is unlikely to deny the request because the bank is more likely to get repaid if the project is completed.